#FollowWomenWednesday: Why It Succeeded — And Why It Won’t Last

How long could #FollowWomenWednesday last? This was one of my questions in the first few weeks of this hashtag meme, which aimed to create more gender equality on Twitter.

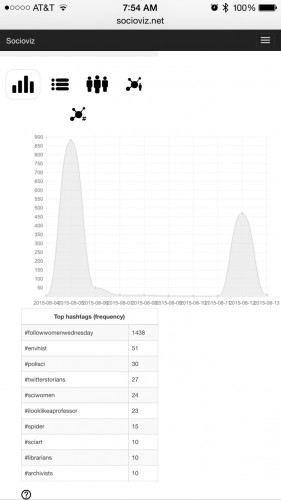

Initially I was not optimistic. Hashtags are usually flashes in the pan, and it was unclear how many Tweeps who participated in the first two Wednesdays would come back for more. I didn’t have many assessment tools during that time, but then I discovered SocioViz, a free Twitter analysis tool that can search up to 5,000 tweets over a two-week period.

Here’s what I found out: rather than declining precipitously after the first #FollowWomenWednesday, the number of tweets containing the hashtag oscillated:

#FollowWomenWednesday tweets, August 5 and August 12, 2015

August 5: ~880

August 12: ~460

August 19: ~630

August 26: 323

September 2: 571

On “surge” Wednesdays, new groups of people were clearly “discovering” the hashtag through various means. This was sometimes due to a single person’s influence: on August 19, for example, a neurologist and life/wellness coach named Romila “Dr. Romie” Mushtaq wrote a blog post about #FollowWomenWednesday, which brought new users to the project.

At other times, #FollowWomenWednesday benefitted from other hashtag memes: on the first Wednesday in September, 1/4 of the #FollowWomenWednesday tweets were paired with #whitemalesyllabus and #allmalesyllabus, which resulted in a user spike.

#FollowWomenWednesday tweets, August 12 and August 19, 2015

The down days suggested that the novelty was wearing off, or that many academics were heading back into the classroom and no longer had as much time to devote to Twitter.

Despite these oscillations, however, it has become clear that #FollowWomenWednesday will likely peter out in the next few weeks. SocioViz has been a bit glitchy today so I don’t have raw numbers but from what I saw via a hashtag search, yesterday’s numbers fell to around 100.

Why #FollowWomenWednesday was successful for a time:

Tweeters were invested in the project

For those who checked their Twee-Q scores way back in the beginning, the epiphany of their own unequal retweeting was a spur to action.

For others, the hashtag was invigorating. It gave them the opportunity to promote friends and colleagues whom they admire, and to find new, interesting women to follow.

And the questions that #FollowWomenWednesday asked — which of our practices (following, posting, reposting, retweeting) contribute to continued sexism on Twitter and Facebook? How are we personally responsible for creating inequalities in these contexts? — were the kinds of questions that interest intellectuals, especially those who frequently use social media.

These are important questions to ask in general, but they are especially important for academics, for whom Facebook and Twitter comprise personal but also professional communities of colleagues and contacts.

Academic tweeters have an interest in creating online communities

Although only around 18% of Americans use Twitter, the number of academics, public historians, journalists, and writers who use it is growing.

#FollowWomenWednesday showed that some people (mostly women–see below) have an interest in creating more diverse online communities. This is a worthy goal in and of itself, but it also dovetails nicely with our professional goals as intellectuals.

Because while social media communities are engaging and enlightening, they are also culturally — and often professionally — powerful. If a public intellectual with a huge reach (like Ta-Nehisi Coates, for example) retweets me, or has a conversation with me on Twitter, I benefit from that connection in multiple ways.

- First, I have a stimulating conversation with a smart person.

- Second, that conversation is read, liked, and retweeted by a much larger constituency than I usually have access to.

- Third, that conversation could bring me new followers, or new connections that could then open up other opportunities both on and offline.

Those who participated in #FollowWomenWednesday clearly cared about who they follow, share, and retweet – and who follows, shares, and retweets them.

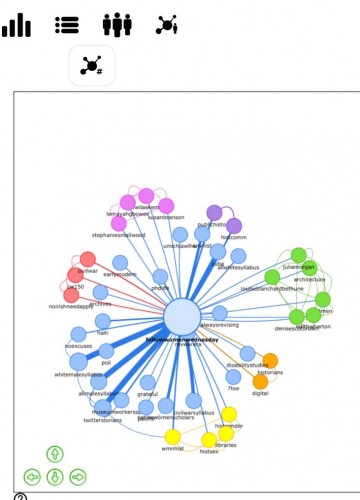

Related hashtags, September 2, 2015

Why #FollowWomenWednesday did not go viral — and why it won’t last much longer

As noted above, there is a fatigue factor with these things.

In addition, the fall is a very busy time for many academics: ’tis the season of new classes, conferences, and the job market melee.

But there are other reasons too. In addition to tracking the raw numbers, SocioViz also allows you to track other hashtag trends: the most influential users (determined by number of retweets and mentions), the top hashtag networks (paired or grouped hashtags), and the network of user interactions (individual Tweeters and the communities to which they are connected).

Looking at #FollowWomenWednesday’s stats in these areas suggests why it did not — really, could not — go viral, nor sustain a high level of participation after that first week.

No Stars

In a world in which one tweet from Miley Cyrus can get a television show renewed, going viral necessitates the participation of at least one Twitter “star” – someone who has followers in the six-figure range, and who actively tweets.

Despite the fact that many participants in #FollowWomenWednesday have tweeted the handles of high-profile public intellectuals, women in media, and actors – none of these women have paid it forward. Also, a significant number of high-profile public intellectuals (like, say, Jill Lepore) are either not on Twitter, or tweet so infrequently (ex: Doris Kearns Goodwin) that they do not have much of a Twitter presence at all.

Only a Handful of Men

In the most recent 100 tweets using #FollowWomenWednesday on September 2, 80% were tweeted by women, 10% by institutions, and 10% by men. Without more willing and enthusiastic participation by the entire Twitter and academic community, the hashtag had no hope of going viral or thriving in the long term.

Only Academics

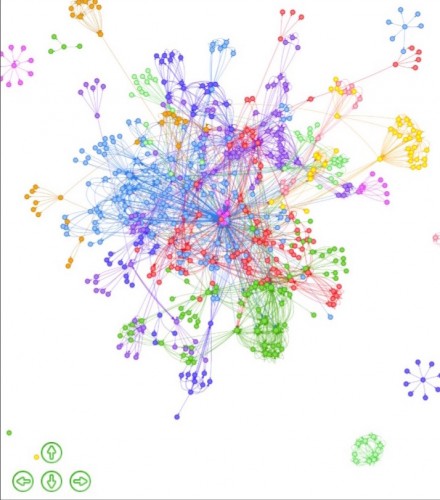

#FollowWomenWednesday User Network, August 5 and 12, 2015

As we can see from user network maps, #FollowWomenWednesday did not often make the leap from academic circles to other groups.

This is likely because #FWW was feminist, activist project. To participate in #FWW, you had to like thinking analytically about social media, and want to work toward creating gender equality in this context. Such projects appeal to academics – and perhaps not to many other people.

Also, as we have almost daily proof, the academic world is miniscule. There are probably two degrees of separation between any given academic and another. We see this in #FollowWomenWednesday because many participants shared the same handles over and over again, or just gave shout-outs back to those who had promoted them. When this happens, instead of generating new circles, the user network just becomes a more densely packed sphere.

The Takeaway

Very few hashtag memes actually go viral, or last much longer than a few days. Those that do appeal to a broad constituency and then disappear. #BlackLivesMatter is a rare example of a hashtag meme that quickly gained cultural currency and was then converted into an organizing refrain within racial justice movements.

User Network, September 2, 2015. A less tightly connected circle, but still not often leaping beyond the Twitter communities of certain academic “nodes.”

#FollowWomenWednesday was a different sort of hashtag meme. It came around on a regular basis and therefore it had some staying power. And its participants were always enthusiastic and invested in #FollowWomenWednesday’s goals.

But #FollowWomenWednesday clearly did not speak to a large enough or diverse enough group of Twitter users to become a long-term social media project.

In the end, #FollowWomenWednesday proves that campaigns for gender equality in social media will only endure if we stop believing that this is women’s work. Men — and cultural institutions that represent both men and women — need to join women in this project; we need to understand gender equality as our collective responsibility.