Lighting out for the Territories

Why do so few historians talk about the American Civil War in the West? And by “the West” I don’t mean the trans-Mississippi. I mean the vast stretches of high desert and the extensive mountain ranges west of the 100th meridian, where elevation and aridity make everything a bit more difficult: breathing, walking, growing crops, keeping animals alive and wagon wheels turning.

Some people assume that no one talks about the West because there weren’t any Civil War battles there. This isn’t true.

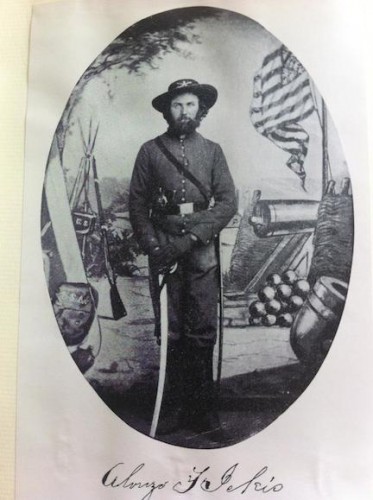

Alonzo Ickis, an Iowa farmer turned Colorado gold miner who fought for the Union in New Mexico, 1861-1863.

There were several clashes between Union and Confederate troops early in the war—at Valverde, and then at Apache Canyon and Glorieta Pass in New Mexico Territory in 1862. The armies here were miniscule (2,000-3,000 men) compared with the massive armies in the trans-Mississippi and the eastern theaters, but their battles were hard-fought, and definitive. And when the Confederates retreated Union troops continued their ongoing battles against Native peoples in the region; these were as significant to the Union war effort as campaigns against Confederates. The climate and topography shaped all of these fights to an unusual degree; we can learn a great deal about why military strategies succeed and fail in different landscapes by examining the Western theater.

Others—most conspicuously Gary Gallagher, in an interview with the Civil War Trust—say that no one talks about the West because we don’t need to: the wartime events there do not matter in the overall history of the conflict. Such a dismissive assertion cannot be taken seriously; and it isn’t true either.

In the 1840s and 50s, American politics of imperialism and the increasingly bitter sectional debates about the expansion of slavery were focused on the western territories. The imagined futures of these lands continued to shape both Union and Confederate nationalisms throughout the war, inform political decisions and legislative acts, and influence military strategies in all theaters.

Monument to Union soldiers from Colorado in front of the capitol building in Denver

Clearly, we need to talk more about the Civil War in the West. Some scholars have already begun to do so. Historians Donald Frazier, Jerry Thompson, and John Wilson have written about the Union and Confederate war efforts in the New Mexico and Arizona territories, while several scholars of western Native American history (Pekka Hämäläinen, Brian DeLay, and Karl Jacoby) have given some attention to the Civil War era in their books. Ari Kelman’s 2014 Bancroft Prize-winning A Misplaced Massacre argues for understanding the Civil War as an imperial enterprise in this region; and a forthcoming edited volume containing essays on the war and Reconstruction in the West (University of California Press, 2015) suggests that paying attention to the Civil War West reveals “a larger, unified history of conflict over land, labor, rights, and the limits of governmental authority in the United States.”

I will be adding my own voice to these conversations through my new book project, tentatively entitled Path of the Dead Man, which will weave together the wartime stories of Union and Confederate soldiers, Apaches, Navajos, and Southwestern civilians. Over the next few months I will be traveling throughout the West, doing research in state and university archives in Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas. I will be reading through newspapers, letters, diaries, and business records, and looking at photographs, maps, material culture, and the landscape itself in order to determine the nature of the Civil War in the West.

I will also be driving (and sometimes biking) the region’s roads. Extraordinarily long marches over mountains and through deserts characterized the war in the West. Path of the Dead Man will be a military and a cultural history; it will also be an environmental history of landscapes of mobility. I will be tracking one Union soldier’s 1861 journey from Cañon City, Colorado to Santa Fe; following the route of the 1864 Long Walk of the Navajo from Canyon de Chelly, Arizona to Bosque Redondo, New Mexico; and tracing the many steps that Confederate General Henry Sibley’s Brigade took on their 1862 retreat from Albuquerque, New Mexico back to San Antonio, Texas.

Remnants of the Santa Fe Trail outside Fort Union, New Mexico

I will be writing about archival finds and historic sites, and will be posting photo galleries as I go. The blog will become a kind of research diary and through it I will work out ideas and experiment with arguments and methodologies.

This doesn’t mean that Historista will now be all Civil War, all West all the time, however. I’m sure I’ll come across other weird and surprising things during this trip that I will feel moved to write about. And the next season of The Vampire Diaries begins on October 2.